In this section:

OVERVIEW

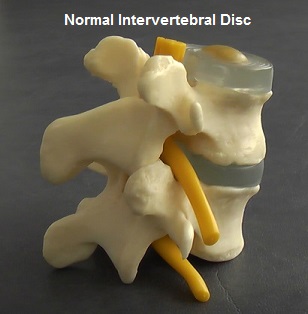

The intervertebral discs provide cushioning and spacing between the bones, joints and nerves in the spine. Various problems can occur to the discs as result of injury or degenerative change over time.

Disc problems can categorised as follows:

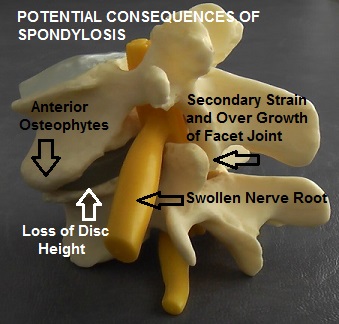

Loss of Disc Height (Spondylosis):

Discs can become thinned (spondylosis), contributing to approximation and increased load on the facets joints along the spine and encroachment of the spinal nerves.

Torn Disc (Annular Tear):

Tears in the outer wall of a disc can occur due to trauma and / or adverse micro-shearing movements due to poor core stabilisation (See below for more detailed information).

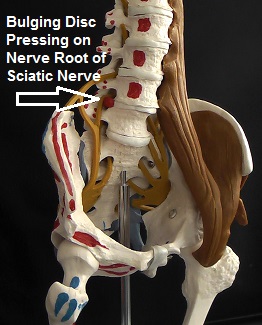

Bulging Disc (Disc Herniation or Prolapse):

An outpouching of the normal contour of a disc can exert pressure and irritation on the neighbouring spinal nerve to cause sciatic pain.

The main treatment we offer at Spine Plus for bulging discs and spondylosis in the neck or lower back is our non-surgical, non-invasive, computerised, IDD Spinal Decompression Programme. This involves a course of sessions on our IDD Therapy machine to gently and precisely stretch specific disc segments in order to promote natural disc healing, coupled with a core strengthening exercise regime to improve spinal stabilisation. Where appropriate we often add in other treatment modalities such paraspinal dry needling (acupuncture) to the deep muscle of the spine to further promote healing and reduce tension on the damaged disc(s). We are currently one of the largest and most experienced providers of IDD Therapy in the UK, with two IDD machines located at our Chigwell and Fitzroy Square clinics. It is important that all potential patients have an initial assessment with one of our clinicians, including a review of their MRI scan(s) to assess their suitability for IDD.

Please view our IDD Therapy page for more information.

One of the advantages of IDD Therapy is that it is non-invasive and possesses very little risk of harm. However where IDD therapy is inappropriate or proves not to be effective, we aim to assist clients in deciding on the most appropriate further options for their degenerative disc condition(s).

The following information and outline of interventional procedures is provided for information purposes only. The list of injections and surgical procedures may not be complete and we ultimately recommend guidance from a spinal surgeon or medical consultant.

DISC & ANNLAR TEARS

In order to understand what an annular disc tear is and how it can affect the human body, it is important to first understand what an intervertebral disc is and the essential functions that it is responsible for.

Intervertebral Disc and Annular Disc Tears

The human spine is made up of numerous bones or vertebrae that help to support the head and torso. Each pair of vertebrae has an intevertebral disc, which serves as a pressurised cushion between them. In all, the human spine has 23 discs that lie in the cervical region, thoracic region and the lumbar region of the spinal column.

An intervertebral disc forms a cartilaginous joint at each vertebra, enabling them to move so that a person can bend and twist. The disc also functions as a fibrous tissue that helps to hold the numerous spinal vertebrae together. Each disc can further be divided into two main parts, namely the annulus fibrosus and the nucleus pulposus.

- Annulus Fibrosus: This is the tough outer capsule of an intervetebral disc and is made up of multiple fibrocartilage that contain a combination of white fibrous tissue as well as cartilaginous tissue. The layers of the annulus have several nerve fibres that are extremely sensitive to pain.

- Nucleus Pulposus: This is a gel-like substance that is contained inside the disc and is protected by the outer covering of the annulus. The nucleus pulposus does not have any nerve fibres supplied to it.

The annulus and the nucleus together make up an intervertebral disc. This disc is responsible for absorbing any kind of shock or impact that is felt by the body in the course of regular physical activities. The disc also helps to keep two vertebrae separated from each other so as not to cause friction between the bones.

The annulus of a disc is a ligament and as such it is susceptible to tears. When the annulus of a disc gets damaged, or any of the layers of the annulus are torn, it is known as Disc and Annular Tears or simply annular disc tears. When the annulus tears, the soft gel-like substance inside the nucleus can start leaking from the annulus, leading to a herniated disc. Since the outer layers of the annulus contain several nerve fibres, an annular tear can often be quite painful.

Types of Disc And Annular Tears

Disc and annular tears can be categorised into three main types, which are:

- Rim Lesions: When a tear occurs in the outer-most fibres of the layers of the annulus, it is called a rim lesion. Typically, this type of annular tear is horizontal in nature. While the natural degeneration of the intervertebral disc is often the cause of annular tears, rim lesions are usually said to occur due to physical trauma. Discs that have the presence of rim lesions generally degenerate faster than healthy discs.

- Radial Tears: The second type of disc and annular tear is classified as a radial tear. Unlike a rim lesion that occurs in the outer-most layer of the annulus, a radial tear is one that occurs in the inner-most portion of the disc, namely the nucleus pulposus. It typically advances in a radial or outward path, hence the name. Radial tears are said to occur due to the natural aging of the disc, but may also be sustained due to impact or injury. Since these tears occur in the centre of the nucleus where there are no nerve fibres, they may often be asymptomatic. Radial tears can further be classified into different grades, depending on the nature and severity of the tear. Grade 0 refers to a healthy disc, in which there is no seepage from the nucleus. Grade 1 to Grade 4 radial tears refer to those tears in which the material of the nucleus seeps into the various layers of the annulus, starting from the innermost layers in Grade 1 and travelling to the outermost layers, which is a Grade 4 tear. The most severe kind of radial tear is Grade 5, in which the nucleus material has seeped through the entire annulus, breaking the disc wall and seeping out of the damaged disc.

- Concentric Tears: The third type of annular tear is known as a concentric tear. The annulus pulposus of an intervertebral disc has numerous layers of collagen called lamellae. When a tear occurs between the lamellae, splitting the annulus, it is called a concentric tear. This type of disc and annular tear is usually associated with physical trauma of a repetitive nature. Concentric tears typically occur in the outer layers of the annulus and can hence be extremely painful.

Diagnosis of the above types of annular tears is typically done by a test known as discography. In this test, a type of dye is injected into the disc and the disc is then pressurised intentionally to determine whether the dye spreads and any pain occurs. The presence of pain is an almost certain indicator of a damaged or torn disc. However, discography is quite an invasive procedure and can be excruciatingly painful. This is why researchers have tried to find, and have subsequently developed, another diagnostic tool for torn discs, known as HIZ (High Intensity Zone) Sign.

Basically, an HIZ sign is a finding on an MRI scan that is thought to be a good indicator of a damaged disc. Typically, when a radial tear merges with another concentric tear or a rim lesion, the condition will appear on an MRI as an HIZ Sign, thereby enabling the medical practitioner to correctly diagnose a disc and annular tear.

Causes of Disc and Annular Tears

The outer annulus of an intervertebral disc is made up of several collagen fibres known as lamellae, which are inherently very strong in nature, thereby making the annulus a tough capsule that can withstand a great deal of impact. During the course of regular spinal movements, the central nucleus of the disc bears the maximum stress of the body, thus ensuring that the annulus does not become overburdened. However, as a person ages the annulus starts to deteriorate in strength and also loses its flexibility and pliability over the course of time. The discs thus become weakened due to the natural process of aging, which in turn makes them more susceptible to injury and tears.

By the time a person reaches the age of 30, deterioration in the natural strength of the annulus starts to occur. Thereafter, if the body suffers any kind of physical trauma, this can lead to disc and annular tears. Apart from the natural degenerative process of getting older, there are various things that can cause annular disc tears, which are

- Sudden harsh physical trauma: In younger individuals who typically have a strong annulus, harsh physical trauma or impact of a sudden nature can result in tears in the annulus fibrosus. The strong impact could arise from a vehicular or other type of accident and is also quite common in people who engage in contact sports.

- Nature of occupation: People who are in an occupation that involves a considerable amount of heavy lifting, pushing or pulling, as well as a significant degree of strenuous physical activity, may be more prone to disc and annular tears than those who are not in such occupations. Constant physical activity can cause the annulus to develop tiny rips or holes, which can become bigger annular disc tears over time.

- Being obese: Being obese or overweight can also be a major reason why annular tears develop. Since the human spine is responsible for bearing the maximum weight of the body, excessive weight can cause tremendous stress on the spine, which in turn leads to the compression of the intervertebral discs. The discs may thus degenerate faster, which can cause disc and annular tears.

- Genetics: If you have a genetic predisposition to weak annular collagen material, then you could be born with an annulus that is weaker than that in others. In such situations, even slight physical impact that appears seemingly harmless may lead to disc and annular tears.

Some more risk factors that have been typically associated with disc and annular tears include high impact exercising, extreme sports and excessive smoking.

Symptoms of Disc and Annular Tears

Diagnosing a medical condition is often dependent on the symptoms that the patient is experiencing. This is why it can often be extremely difficult to diagnose disc and annular tears as the person suffering from them may not be experiencing any pain or other symptoms at all. The annulus fibrosus has three different layers, which are the inner layer closest to the nucleus, the concentric middle layer, and the peripheral outer-most layer. It is only the outer-most layer of the annulus that is supplied with nerve fibres, which means that if any tear occurs in this layer, the person is likely to feel considerable pain. Even if the tear occurs on the inner or middle layer but the gel like substance inside the nucleus makes its way to the outer layers, the person will feel pain. However if the annular tear is in the innermost layer or the middle layer, which do not have nerve fibres, then the person suffering from the tears may not experience any painful symptoms at all.

In situations where the annular disc tears are symptomatic, the common symptoms that can be experienced are:

- Pain: Disc and annular tears can cause a great deal of pain if the nucleus pushes against the annulus or if the substance inside the nucleus of the disc starts to seep into the outer annular layers. Depending on which of the discs are torn, pain will be felt in different parts of the body. If a cervical disc is torn, patients could feel considerable pain in the neck area, as well as through the shoulder and down into the arm as well. If a lumbar disc is torn, it can result in pain in the lower back area, which can also extend into the buttocks, legs and sometimes down into the feet as well. The degree of pain differs from person to person and may depend on their pain threshold as well as the extent of the annular tears.

- Tingling and numbness: Once again, depending on the location of the torn intervertebral disc, the patient may feel tingling sensations similar to pins and needles, as well as numbness in their arms and legs. The disc and annular tear can also result in severe weakness in the limbs, making functional use of them difficult. Different muscles may weaken depending upon which nerves have been affected. Muscle spasms are also felt by numerous people suffering from disc and annular tears.

- Swelling: The nerves that are affected by the disc tear may become inflamed, leading to swelling in different parts of the body, which once again will be determined by which nerves are impacted.

Most people who suffer from annular disc tear symptoms will notice that their symptoms and pain often becomes worse when they perform physical activities such as bending, sitting, lifting things, or even if they sneeze hard. This typically occurs because these movements increase the pressure on the damaged disc. On the other hand, the simple act of standing can often relieve the pressure on a torn disc, which will lessen the pain noticeably.

Treatment and Prevention of Disc and Annular Tears

Disc and annular tears can be treated with non-surgical options as well as disc tear surgery, such as:

- Non-surgical options for disc and annular tears: Doctors will often advise that people who have disc tears, but are not experiencing any symptoms, may not need to resort to any kind of treatment as long as their condition is asymptomatic. That being said, treatment could become necessary if painful symptoms occur. In such situations, the first line of treatment is a non-surgical approach that does not involve invasive surgery. Patients are typically advised to rest and undergo physical therapy. Anti-inflammatory drugs may also be advised for patients who have a significant amount of swelling to reduce the inflammation and the accompanying pain. Ice and heat therapy can also help to reduce the symptoms of annular disc tears and could be advised as treatment. Massage therapy has also proven to be quite effective in reducing the symptoms of disc tears, as have alternative treatments such as acupuncture and chiropractic alignment.Various exercises that enable patients to strengthen their core muscles to increase stability may also be recommended. This includes yoga, swimming, brisk walking, and other forms of light aerobic workouts. It is extremely important for patients to understand and employ proper body postures so that the stress on their spine can be reduced, which in turn lowers the pain and symptoms felt due to disc and annular tears.

- Surgical treatment for disc and annular tears: Although annular disc tears can be quite painful, the good news is that most of these tears heal on their own without the need for invasive surgery. The body’s natural healing process results in the formation of scar tissue in the peripheral layers of the annulus, effectively plugging the holes or tears so that the gel-like nucleus substance does not leak and cause pain. However, in some cases, the tears may be quite large and may not heal on their own. If non-surgical treatments do not help to reduce the pain, then disc tear surgery could be advised as a last resort. When disc tear surgery is unavoidable, you may expect to undergo one of the following three types of surgeries.

- Open back surgery: This is the most invasive type of disc tear surgery and involves the cutting open of your skin to reach the damaged disc. The torn disc is usually removed and the pair of affected vertebrae is fused together.

- Laser disc decompression surgery: Although this is a surgical procedure, it is less invasive than open back surgery. This type of treatment involves the use of a laser that is employed to shrink the damaged disc so that the tear in the disc can be reduced to negligible proportions.

- Endoscopic disc tear surgery: This, too, is a minimally invasive procedure that involves the use of a special surgical tool that is inserted into the affected area of the body through a tiny incision. The surgical tool is then used to locate and seal the annular disc tear, thereby preventing the nucleus material from leaking into the annulus and causing pain.

In order to avoid disc tear surgery, which could result in a long and tedious recovery process, it is best to try and prevent disc and annular tears in the first place. This can be done by exercising to enhance core muscle strength and increase flexibility. Try and maintain your ideal body weight and give up smoking because nicotine can cause faster degeneration of intervertebral discs, thereby increasing your risk of disc and annular tears.

SPINAL INJECTION THERAPY

Lumbar Caudal Epidural

A steroid and pain killer are injected into the epidural space (space around the spinal nerve), via the sacral hiatus (small channel at the base of the sacrum just above the buttock cleft).

Cervical Epidural

An injection of a pain killer and anti-inflammatory steroid is inserted into the epidural space of the neck. It is used to ease pain and inflammation often associated with nerve root entrapment and degenerative disc disease.

Nerve Root Block

An injection is performed under x-ray guidance, whereby a pain killer and an anti-inflammatory steroid is injected very near to a specific nerve root within the spine that is transmitting a large amount of pain due to injury or pressure on that nerve root.

(Therapeutic) Facet Joint Injection (steroid)

An injection of a numbing pain killer and anti inflammatory steroid is inserted into the small facets joints on one or both sides of a vertebral level. The procedure is performed under x-ray guidance and commonly used when the wear and tear of the facet joints is thought to be responsible for a patient’s pain. The injections can be used for diagnostic purposes (pain killer only) to determine if a particular facet joint is the source of pain, or for therapeutic purposes to treat the source of the pain. When such injections work, pain relief can be achieved for several months or more, after which the procedure can be repeated. Some clinicians raise concerns that injecting a steroid into synovial joints (including facet joints) may accelerate the rate of degeneration of healthy cartilage within the joint and so may therefore wish to reserve this technique only for patients with severely degenerate joints or if there is a very good chance of pain relief that will outweigh any risks.

(Therapeutic) Sacro-iliac Joint Injection (Steroid)

An injection that is usually performed with live x-ray guidance into one or both sacroiliac joints (joints located at the base of the spine between the sacrum and the pelvic bones). Sacro-iliac joint pain is thought to be the source of low back and buttock pain and can even mimic pain from other structures such as lumbar discs, nerve roots and facet joints. A mixture of a steroid and pain killer is injected into the joint with the intention of providing long term relief and reduction of inflammation within it. Some clinicians raise concerns that injecting steroids into synovial joints (including sacro-iliac joints) may accelerate the rate of degeneration of healthy cartilage within the joint and so may therefore wish to reserve this technique only for patients with severely degenerate joints or if there is a very good chance of pain relief that will outweigh any risks.

Radiofrequency (joint) Denervation

This is a procedure during which the nerves innervating a joint are burnt using a radio frequency probe. This stops pain signals being generated from the joint. The nerve endings eventually grow back, usually after a few months, after which the procedure may be repeated.

Pulsed Radiofrequency Denervation

This is a procedure similar to joint radio frequency denervation. However, rather than targeting the facet joint, this procedure is usually used to target the nerve root or branches of it. Also, rather than burning all the nerve fibres, pulsed radio waves are used which do not have any heating effect but selectively “stun” the pain carrying fibres.

Intradiscal Electrothermal or Radiofrequency Modulation

There are a number of procedures available that involve passing heating wires and / or radiofrequency electrodes into the disc with the intention of ablating painful nerve fibres within the disc wall and / or sealing tears in the disc wall.

Intradiscal Chemical Modulation

This procedure involves an injection of drugs, such as corticosteroid or Methyl Blue, into a intervertebral disc with the intenton of blocking nerve signals or stabilising the inflammatory process within a painful disc.

Prolotherapy (Proliferation Therapy)

Prolotherapy, sometimes referred to as sclerosing injections, is most commonly undertaken by orthopaedic physicians. A solution containing sugar and phenol is injected into ligaments supporting the spine with the hope of stimulating proliferation of collagen in order to strengthen the ligaments, stabilise the spine and reduce pain.

SPINAL SURGERY PROCEDURES

(Posterolateral Gutter) Spinal Fusion

This is generally regarded as the most “tried and tested” method for surgically fusing together two adjacent spinal segments (vertebrae). It involves a three to six inch incision through the midline of the back. A bone graft is harvested from the patient’s hip bone (iliac crest) and attached between the “transverse processes” on each side of the vertebrae (such as L4 and L5). Muscles that have been partially dissected during the procedure are then reattached over the graft in order to create tension. Screws, rods and other surgical instrumentation may also be used to encourage a solid fusion by holding the vertebrae in place as the graft heals over time. Whilst the procedure has a long and trusted history, the technique on its own does not offer a way of restoring intervertebral height resulting from a severely thinned disc (spondylosis) and may therefore be reserved for conditions such as sponlylolisthesis, where one vertebrae has slipped forward over another but where the intervertebral disc itself is relatively healthy and does not need to be removed (partially or wholly). The surface area for the graft is smaller and is not exerted to the same amount of body weight compression compared to the “interbody” methods of fusion. This avoids the small risk of graft retroplusion associated with interbody fusion and means the graft does not benefit from compressing forces encouraging bone growth, as opposed to Wolff’s law which argues that bones heal better when under compression. This may explain why the chances of achieving solid fusion are reported as being less likely than with the more recently developed interbody methods of fusion.

Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (PLIF)

PLIF is a surgical procedure for fusing together the vertebral bodies of two lower back spinal segments (vertebrae). Most of the damaged disc that lies between the vertebral bodies is removed and replaced with bone graft. This lifts pressure from pinched nerve roots and enables a solid bone mass or “fusion” to form, thus stabilising the spine. With “posterior” interbody fusion, the surgical approach is made posteriorly in the midline of the back. Muscles either side of the spine are stripped away and the laminae and interspinous process from one vertebra are removed so that access can be gained to the intervertebral disc space. The surgeon may also supplement the PLIF procedure with a “Posterolateral Spinal Fusion” whereby a series of screws and rods, as well as bone grafts, are inserted in the back and sides of the vertebrae to provide increased stabilisation.

Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (ALIF)

ALIF is a surgical technique for fusing together the vertebral bodies of two lower back spinal segments (vertebrae). Most of the damaged disc that lies between the vertebral bodies is removed and replaced with bone graft. This lifts pressure from pinched nerve roots and enables a solid bone mass or “fusion” to form, thus stabilising the spine. Surgical access to the disc space is gained from an “anterior” incision through the abdomen. This has the advantage of leaving the bone, muscles and nerves at the back of the spine undisturbed (unlike with other forms of fusion). An anterior approach also allows for a much larger implant, providing better initial stabilisation. However making an incision through the stomach does pose some risk to the important structures in that area, such as major blood vessels, which can require particular expertise from the spinal surgeon and may require an additional (vascular) surgeon to be present during the procedure. For men undergoing an L5/S1 fusion there is also a slight risk (about 1%) of damage to nerve endings controlling valves during ejaculation, meaning that ejaculate can be expelled into the bladder (“retrograde ejaculation”). Erectile function, sensation of ejaculation and orgasm are unchanged, but it can make conception very difficult. For some people a second surgical procedure is planned to take place a week or so after their ALIF surgery to insert screws and/or rods into the back of the spine to provide posterior fixation and additional stabilisation.

Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF)

This is a minimally invasive surgical procedure for fusing together the vertebral bodies of two lower back spinal segments (vertebrae). Access to the intervertebral disc space is gained through a small incision in the patient’s side. This allows major muscles of the back to be avoided. Most of the damaged disc that lies between the vertebral bodies is removed and replaced with bone graft. This lifts pressure from pinched nerve roots and enables a solid bone mass or “fusion” to form, thus stabilising the spine. The procedure may be performed on an outpatient basis, however it is not suitable for all conditions where spinal fusion is an option. For example, it cannot be used on the lowest disc space (L5/S1). A particular risk from the lateral approach is the possibility of damage to the lumbar plexus of nerves serving the thigh (quadriceps) muscles. This risk is minimised by use of an electromyograph (EMG) monitor to warn the surgeon if they are near a vulnerable nerve.

Trans-Foraminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion (TLIF)

This is a surgical procedure for fusing together the vertebral bodies of two lower back spinal segments (vertebrae). Most of the damaged disc that lies between the vertebral bodies is removed and replaced with bone graft. This lifts pressure from pinched nerve roots and enables a solid bone mass or “fusion” to form, thus stabilising the spine. With the trans-formaminal approach, the incision is made posteriorly to one side of the midline, with the procedure involving removal of one the facets joints that connects the two vertebrae together. The main theoretical advantages in comparison to PLIF are that this allows for greater visualisation into the disc space, increased disc removal, a larger implant / bone graft and greater distraction of the disc space. However this must be weighed against the fact that an entire facet joint from one side of the spine is removed (rather than a portion of each facet from either side of the spine as with PLIF).

Posterior Lumbar Dynamic Stabilisation

The instrumentation used during this type of spinal surgery has evolved from the pedicle screws and rods traditionally used during posterior spinal fusion. However rather than using rigid screws and metal rods, flexible screws and rods with moving parts are now used instead. The goal of such surgery is to offer stabilisation of an intervertebral segment without fusion, i.e. allowing controlled motion between the two vertebrae. By preserving near normal movement at the operated level, the hope is to avoid the increased strain on adjacent levels of the spine that can develop several years after traditional fusion operations.

Lumbar Decompression (Laminectomy)

The lamina is the name of part of a vertebral segment that forms a bony ring or “canal” around the spinal cord and spinal nerves. This canal becomes narrowed in conditions such as spinal stenosis, causing encroachment on the spinal cord and nerves. Spinal stenosis most commonly affects older age groups who suffer generalised wear and tear in the spine. Lumbar spinal stenosis affects the lower back and usually manifests as leg pain whilst walking. “Lamin-ectomy” surgery was developed in the early 1900s and involves a three to five inch incision being made in the lower back. The paraspinal muscles are dissected off the lamina on both sides of the spine, the lamina and spinous process are then completely removed, effectively making the spinal canal at that segment into a semicircle rather than a ring of bone, which frees up or “decompresses” the nerves. Success rates for relieving leg symptoms from spinal stenosis is around 70-80%, although a laminectomy is less reliable for relieving back pain. There is around 1 – 3 % chance of complications occurring, such as nerve damage, incontinence and infections. Also there is a risk for some patients that by removing many of the stabilising muscles and ligaments of the vertebra, segments of the spine may become destabilised, leading to chronic back pain and weakness. Stenosis symptoms can also reoccur several years after the surgery, when the degenerative processes that originally caused the stenosis continue. In some cases where stenosis is combined with an unstable segment, stenosis may be prevented from reoccurring by performing a fusion at the same time as the laminectomy. For some people, an alternative to laminectomy is laminoplastly which involves a smaller incision, removing the lamina from only one side of the vertebra, thus preserving more of the supporting structures of the spine.

Lumbar Laminoplasty

A posterior surgical technique developed in the 1980s as a less invasive alternative to lumbar laminectomy, which involves cutting through the lamina on just one side of a vertebra (rather than both sides as in a laminectomy). This creates a hinge in the lamina which is used to widen the spinal canal in order to decompress the nerves. The newly widened canal is then sealed with a bone graft. One of the main advantages of laminoplasty is that, in contrast to a laminectomy, much of the supporting structures of the vertebra, such as the muscles, ligaments and spinous process, are preserved. Despite the fact that lumbar laminectomy is a less invasive alternative to lumbar laminectomy, some surgeons do not offer laminoplasty because it is a more time consuming operation and requires specialised training and equipment, such as an operating microscope.

Lumbar Micro-Discectomy

This is one of the most widely available minimally invasive surgical techniques for treating sciatica due to a pinched nerve root from a herniated or bulging disc. The surgeon uses an operating microscope or glasses (Loupes) in order to reduce the size of the incision needed to access the disc. A small 1 to 2 inch incision is made, slightly to the side of the midline in the lower back. Muscle tissue is gently divided and a small amount of ligament and bone is removed from the lamina and / or facet joint in order to create a window through which the surgeon can remove the bulging portion of the disc and free the trapped nerve root. Lumbar microdiscectomy is reportedly 95% successful at reducing sciatic pain in the leg, with the best outcomes experienced by patients who have had sciatica for less than three to six months. Many cases of sciatica caused by an isolated disc bugle will improve on their own or with the help of physical therapy. If such improvement is going to be achieved without surgery, it will generally happen within 6 to 12 weeks. Therefore, except for severe cases or in the presence of “Cauda Equina Syndrome”, the usual advice is to wait at least 6 weeks before considering surgery. There is a small risk (5 – 10% chance) of the disc bulge reoccurring after surgery, which is more likely within the first 3 months, but can occur several years after surgery. For this reason some surgeons excavate some of the inner part of the disc in addition to removing the bulging portion so that there is less disc material capable of herniating again in the future. This must be weighed against the fact that the more of the disc material removed, the less of it there will be to perform its roles of providing shock absorption and height between the vertebrae and exiting nerve roots. Excessive disc excavation could potentially lead to premature load and degeneration on other structures of the spine, such as the facet joints, several years later.

Endoscopic (Keyhole) Lumbar discectomy

This is a minimally invasive surgery performed through a small diameter tubular device inserted into the back. This technique is most commonly performed to remove the herniated or prolapsed portion of an intervertebral disc that is compressing the adjacent nerve root causing sciatic pain in the leg. Unless using a “transforaminal approach” access to the spinal nerves is gained through the midline, which involves removing small amounts of bone, similar to a microdiscectomy. An endoscopic lumbar disectomy is designed to be even more minimally invasive than using a microscope (microdisctomy). Popularity for endoscopic lumbar discectomy is lacking amongst some surgeons because of concerns it gives limited visualisation of the disc compared to microdiscectomy. The complication rate is also reported as being higher, with the procedure requiring specialised training and being technically more difficult to perform.

Cervical Endoscopic Spinal Surgery.

This keyhole surgery performed on the cervical spine (neck) is most commonly performed to decompress trapped nerves caused by disc herniation. The advent of such technology in the cervical spine has allowed for small incisions and less disruption to muscle and other tissues than with other more invasive techniques, such as disc fusion or disc replacement. Also, whereas removal of the whole disc may once have been a patient’s only option, where appropriate, cervical endoscopic spinal surgery potentially means removing just the herniated portion of a cervical disc is possible whilst preserving its remaining healthy portion. Popularity for endoscopic spinal surgery is lacking amongst some surgeons because of concerns it gives limited visualisation, the procedure requires specialised training and is technically more difficult to perform.

Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy

This is keyhole lower back surgery, whereby an endoscope is used to “walk up the nerve” through the neural foramen (the hole through which the nerve root emerges from the bony spinal canal). This “transforaminal” approach is designed to cause the least amount of disruption to the spinal musculature and bony architecture (even less than traditional endoscopic spinal surgery), whilst at the same time allowing for good visualization. Once in the foramen, the bulging portion of a herniated disc can then be removed in order to reduce nerve root compression.

Trans-Foraminal Endoscopic Lumbar Decompression & Foraminoplasty (TELDF)

As above, this is keyhole lower back surgery, whereby an endoscope is used to “walk up the nerve” through the neural foramen (the hole through which the nerve root emerges from the bony spinal canal). This “transforaminal” approach is designed to cause the least amount of disruption to the spinal musculature and bony architecture whilst at the same time allowing for good visualisation of the nerve, disc, facet and associated ligaments. Once in the foramen, as well as removing bulging portions of intervertebral discs, the neural foramen can be cleared of scar tissue, nerve adhesion and bone spikes with the use of a laser. This type of surgery is not widely available and is technically difficult, requiring specialised equipment and training.

(Automated) Percutaneous Lumbar Discectomy

This is the most minimally invasive of all the surgical techniques, designed to reduce an intervertebral disc protrusion. The procedure is performed under x-ray guidance using a probe or needle inserted into the affected disc. The intention is that there is the least amount of disruption to the posterior spinal muscles and other soft tissues. In reality, the surgeon cannot visualise or access as much of the disc as other with other minimally invasive procedures, such microdiscectomy, and the success rates are not as good, however it may be appropriate for some selected cases. If the procedure fails the patient may be able to move on to others, such as microdiscectomy or endoscopic surgery.

Percutaneous Nucleoplasty

This procedure is usually performed on outpatient basis, involving a device introduced via a hollow needle that removes part of the inner nucleus of an intervertebral disc in order to reduce pressure within it, thereby shrinking the disc so that it exerts less pressure on neighbouring structures, such as pinched nerves.

Facet Replacement or Total Element Replacement Devices for Spinal Stenosis

These relatively new surgical implants are designed to replace the facet joints and associated bony projections that form the posterior architecture of a vertebral segment in the spine. They are primarily used for patients with unresolved facet joint pain and / or spinal stenosis caused by severe degeneration of the facet joints. These devices are designed to preserve movement of the spinal segment, unlike spinal fusion, yet allowing more stabilization and control of movement than a total laminectomy. However these devices are relatively new on the market and do not have the outcome history of more extensively used procedures.

Lumbar Disc Replacement

Offered by some surgeons as an alternative to lumbar fusion, whereby a damaged intervertebral disc (the cartilaginous cushion that sits between two vertebrae) is replaced with an artificial one. Advantages over spinal fusion are that the surgery is less complex and is quicker to perform, with the main theoretical advantage being that movement between the vertebrae is preserved, thus reducing the negative effects of adjacent levels that can occur with spinal fusion. More recent styles of prosthetic discs also offer shock absorbing qualities. Lumbar artificial disc surgery has been available in European countries for around 15 years. Currently only around 50% of spinal surgeons offer the procedure often because they are skeptical about the reality of how much movement the prothesis allows or are concerned about the possibility of the artificial disc becoming dislodged.

Lumbar Interspinous Distraction Devices (e.g. x-stop)

A small prosthetic spacing device is inserted between the spinous process of two adjacent vertebrae to limit the amount of backward bending movement (extension) allowed at that level of the spine, thus preserving the patency of the foramina or tunnels through which the spinal nerves pass. This procedure is designed to alleviate pressure on spinal nerves experienced in conditions such as spinal stenosis. Some reports have also suggested that, in some cases, patients will experience other unintended benefits, such as reduced pressure on painful degenerative discs. The procedure is relatively inexpensive and since the spinous processes lie near the surface of the body, the procedure is relatively uncomplicated and may be performed on an outpatient basis. However it is by no means suitable for everyone, for example people with weakened bones, such as those with osteoporosis, may be at risk of the device causing a fracture to their spinous processes.

Awake State Spinal Surgery

Spinal surgery is performed using an endoscope whilst the patient is sedated, but conscious, to enable the patient to provide instant feedback to the surgeon about sensitive pain provoking structures. This technique is most appropriate in cases where there may be some doubt as to the exact cause of a patient’s pain pattern so that the source of pain can be more accurately identified, rather than relying on what “looks” likely from an MRI scan.

Thoracic Laminectomy (Thoracic Spine Surgery)

Spinal surgery is performed on the middle back (thoracic spine), which is the part of the spine where the rib cage attaches to it. Thoracic spine surgery is far less common than neck or lower back surgery because degenerative changes in the discs and joints are often asymptomatic. It is usually only reserved for rare cases that cause spinal cord compression, progressive neurological deficit and intolerable pain. Thoracic Laminectomy is the traditional historical approach to thoracic spine surgery, involving an approach through the midline of the spine, removing the lamina (portion of a vertebral bone) and pushing the spinal cord aside in order to gain access to degenerative discs. This approach has now largely been replaced by more minimally invasive procedures.

Thoracic Costo-Transverse Ectomy (Thoracic Spinal Surgery)

Spinal surgery is performed on the middle back (thoracic spine), which is the part of the spine where the rib cage attaches to it. Thoracic spine surgery is far less common than neck or lower back surgery because degenerative changes in the discs and joints are often asymptomatic. It usually only reserved for rare cases that cause spinal cord compression, progressive neurological deficit and intolerable pain. During the Costo-Transverse Ectomy procedure, a small amount of a vertebral bone (transverse process) and rib is removed in order to gain access to the thoracic spine.

Anterior Trans – Thoracic Surgery (Thoracic Spine Surgery)

Spinal surgery is performed on the middle back (thoracic spine), which is the part of the spine where the rib cage attaches to it. Thoracic spine surgery is far less common than neck or lower back surgery because degenerative changes in the discs and joints are often asymptomatic. It usually only reserved for rare cases that cause spinal cord compression, progressive neurological deficit and intolerable pain. Trans-Thoracic surgery involves approaching the thoracic spine through the front, either via an open procedure through the chest cavity or in some centers via a minimally invasive procedure involving a number of small incisions, arthroscopes and a video screen (Video Assisted Thoracic Surgery VATS).

Video Assisted Thoracic (Spine) Surgery (VATS)

This minimally invasive surgery for the middle back (thoracic spine) involves an anterior approach through the chest cavity, using a number of small incisions, arthroscopes and a video screen.

Anterior Cervical Discectomy & Fusion (ACDF)

ACDF is one of the standard techniques used to treat degenerative disc disease in the neck (cervical spine). An incision is made through the front of the neck to avoid the delicate nerve endings and spinal cord that would be vulnerable from accessing the spine with a posterior incision. The damaged disc and debris is removed, ready for insertion of a spacer device containing a bone graft. This lifts pressure off of nerve roots and the spinal cord, which may have been caused by the damaged disc. The vertebrae above and below the disc space may be fixed together using a plate and screws. Over time the bone graft knits the two vertebrae together, forming a solid stable bone mass or “fusion”. This is a reliable technique with good success rates and outcomes. However there are concerns that, for some individuals in the longer term, fusing two vertebrae together, thereby eliminating movement at that level, may cause premature wear and tear at other nearby levels of the spine.

Anterior Cervical Corpectomy

This surgery is designed to treat severe cervical stenosis or diseased vertebral bodies in more than one level of the neck. This procedure is completed through an incision in the front of the neck. The surgeon removes one or more vertebral bodies as well as discs above and below each segment in order to fully decompress the spinal canal. The defect is then reconstructed with a bone graft to create a multilevel fusion. This is extensive surgery performed on cases involving significant deformity therefore the risks of complications, such as damage to the spinal cord and nerves, are higher than with other procedures.

Cervical Laminectomy

This type of surgery is completed through a 3 to 4 inch incision in the back of the neck. During the procedure the lamina, spinous process and overlying muscle on both sides of the neck, is removed from one segment of the cervical spine. This effectively turns the ring of bone called the spinal canal, through which the spinal cord passes, into a semicircle. This alleviates pressure on the spinal cord in cases where it was being compressed due to narrowing of the bony spinal canal. The main risk from this operation is that damage could be caused to the spinal cord, nerves and membranes. To help lessen this risk, the surgeon will often use specialised electrodes to monitor spinal cord function during the procedure (Somatosensory Evoked Potentials – SSEP’s). By cutting away much of the supporting muscle, ligament and bone of the operated segment there is also risk of the spine at that level developing instability and deformity. Therefore cervical laminectomy is sometimes performed in combination with cervical fusion surgery.

Cervical Laminoplasty

This is a surgical technique involving cutting through one side of part of a bony segment in the neck called the lamina. The lamina forms part of a ring of bone at each vertebra, called the spinal canal, through which the spine cord passes. This canal becomes narrowed in conditions, such as spinal stenosis, causing encroachment of the spinal cord and nerves. Once an opening has been created in the lamina, this creates a hinge allowing the spinal canal to be widened, with a bone graft then used to seal the opening. An attractive feature of cervical laminoplasty is that, unlike fusion, it preserves movement of the operated segment, therefore lessening the likelihood of premature degeneration of adjacent segments. Also, compared to laminectomy, much of the muscle, ligament and bone is preserved, thus reducing the likelihood of post-operative instability.

However by approaching the cervical spine posteriorly and cutting through the lamina on just one side, it may be more difficult for the surgeon to assess whether or not the canal has been well decompressed. Also, there is small amount of risk of damage to the spinal cord and nerves exposed in the area during such a posterior approach. This risk is less for other procedures used for spinal stenosis that access the spine from the front of the neck, such as Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion (ACDF).

Cervical Disc Replacement

This is the surgical replacement of a damaged or degenerated disc in the neck that, which is initiated by making an incision in the front of the neck. This enables the surgeon to avoid the delegate nerve endings and spinal cord that would be vulnerable from accessing the spine posteriorly. The defective disc is removed, the area cleaned and a new artificial disc is inserted into the disc space. This lifts pressure off of nerve roots and the spinal cord at the same time as maintaining movement at that level of the spine. Artificial disc replacement in the neck is now an established reliable technique, although it is not as “tried and tested” as other more traditional techniques, such as Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion (ACDF). The obvious advantage over ACDF is that it allows movement of the vertebral segment and so reduces the chance of premature adjacent level wear and tear that is associated with fusions.